Renal

WHY USE ULTRASOUND?

Given the contrasting echogenic characteristics of the urinary system, the sonographic examination of the kidney and bladder can provide a wealth of clinical information [1]. Although performed for decades as a comprehensive radiologic ultrasonographic study, in the recent years, there has been growing interest in point‐of‐care renal ultrasonography performed by non‐radiology clinicians. Exclusion of obstructive uropathy is one of the most common indications for renal ultrasonography.

Point-of-care ultrasound is an inexpensive, rapid and repeatable method to diagnose obstructive uropathy, and has the potential to reduce the time from presentation to imaging in the emergency department and expedite clinical decision-making.

Some studies have demonstrated that physicians at all levels of training and experience can obtain similar sensitivity and specificity while performing a simplified scan for the presence or absence of hydronephrosis. [2]

Moreover, the learning curve to correctly identify hydronephrosis with point-of-care ultrasound is quite steep, with as few as 25 practice scans being adequate to develop and retain the skill for detection of hydronephrosis. [3]

It has also been demonstrated that the presence of hydronephrosis on PoCUS was associated with an increased risk of subsequent urologic intervention or complication. [4, 5]

CONTRAINDICATIONS & LIMITATIONS.

Overall, point-of-care US has demonstrated moderate sensitivity (72%) and specificity (77%) in diagnosing obstructive uropathy in large meta-analysis [6]. This may be due to the fact that many of the studies required physicians to perform more complicated scans, as grading of hydronephrosis. It might be argued that simplified approaches, aimed to identify the presence or the absence of hydronephosis, could potentially improve accuracy.

The urinary system is composed of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. [7]

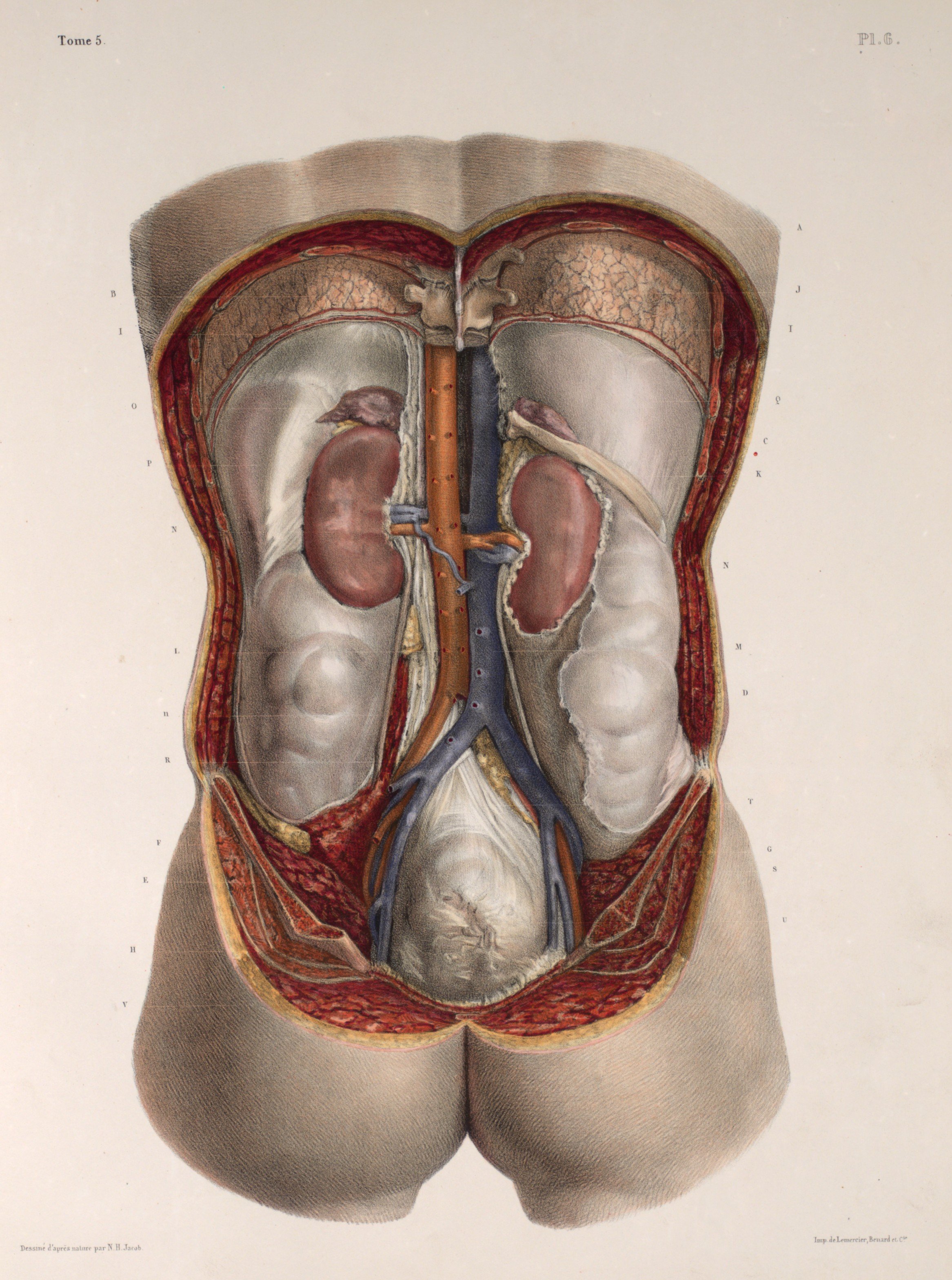

The kidneys are retroperitoneal organs located on either side of the vertebral column from T12-L3. The right kidney is slightly more inferior than the left kidney because of the larger size of the liver relative to the spleen.

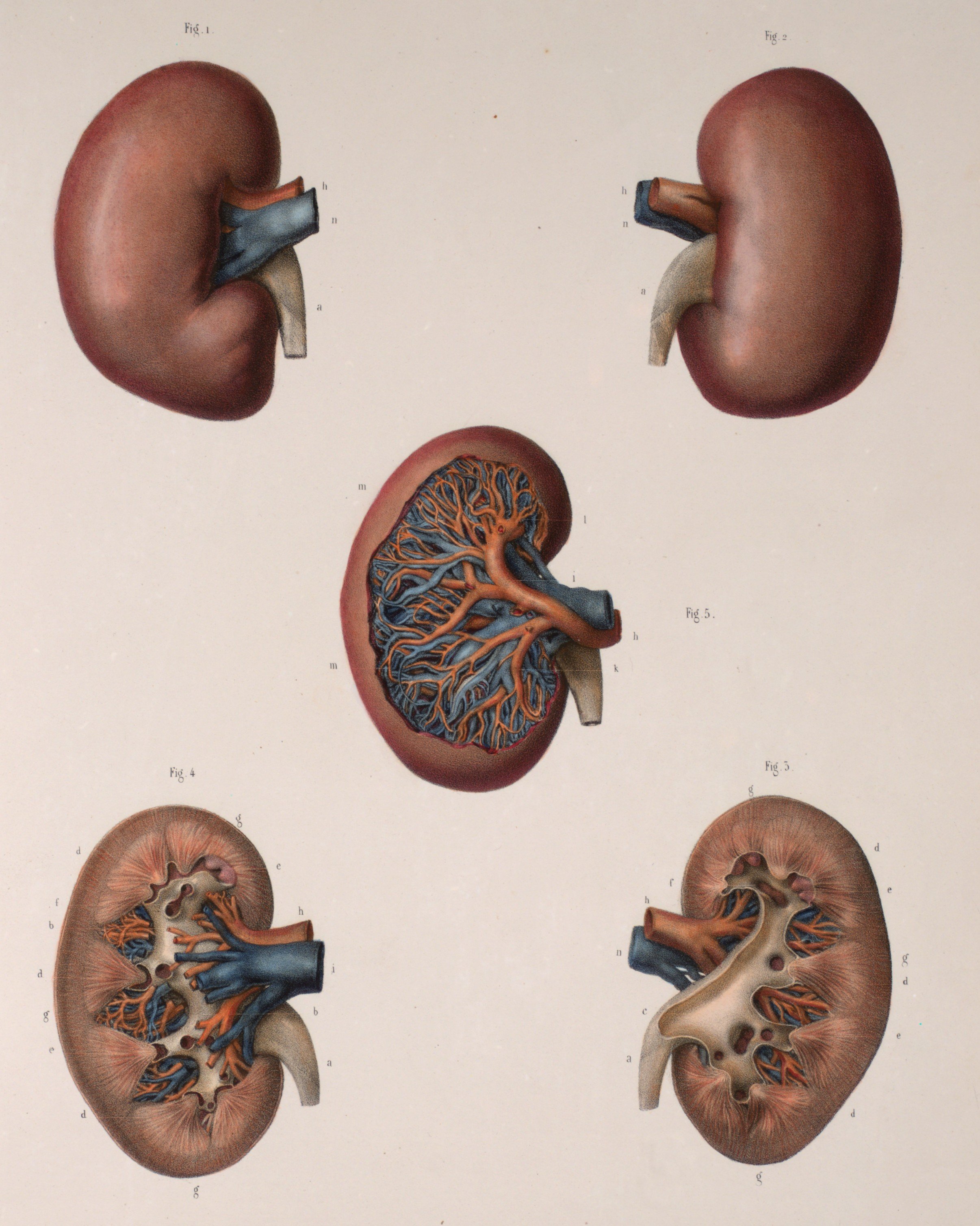

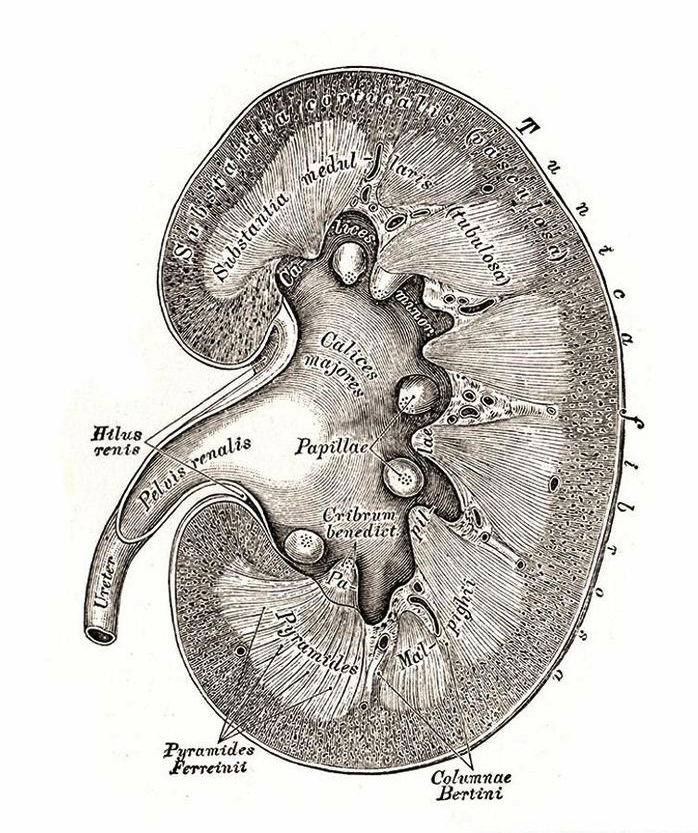

To perform renal ultrasound here are the key renal anatomic structures you should know:

Renal Cortex

Medullary Pyramids

Minor Calyces

Major Calyces

Renal Pelvis

Renal Sinus

Anatomy.

Technique & Views.

POSITION & PROBE

The patient will lie supine.

If having difficulty getting the views, patients can be asked to sit up and be scanned posteriorly or have them lay in the left/right lateral decubitus positions.

THE VIEWS: RIGHT KIDNEY

Longitudinal Axis

Point the probe indicator towards the patient’s head.

Place your probe at the Right Mid-axillary Line around the 10th to 11th intercostal space.

Center the kidney on the ultrasound screen.

Slowly tilt/fan the probe anteriorly and posteriorly to assess the entire kidney.

The normal size of an adult kidney is around 10-11cm in the longitudinal view.

Transverse Axis

Maintaining the longitudinal view of the right kidney, center the kidney on your screen, and then rotate your probe 90 degrees counterclockwise.

The probe indicator should be pointing Posteriorly.

Tilt the probe superiorly and inferiorly to assess the right kidney

The normal size of an adult kidney is around 6 cm in the transverse view.

THE VIEWS: LEFT KIDNEY

The technique for scanning the left kidney is very similar to that of the right kidney. Of note, the left kidney lies slightly superior and posterior compared to the right kidney due to the smaller size of the spleen.

Longitudinal Axis

Point the probe indicator towards the patient’s head.

Place your probe at the Left Posterior Axillary Line around the 8th to 10th intercostal space.

To reach the posterior axillary line, your knuckles should touch the bed.

Visualize the same renal structures you did in the Right Kidney (except instead of the liver, you will see the spleen above the left kidney in this view).

Transverse Axis

Maintaining the longitudinal view, centre the kidney on your screen, and then rotate your probe 90 degrees counterclockwise.

The indicator should be pointing Anteriorly.

Tilt the probe superiorly and inferiorly to assess the entire left kidney.

Visualize the same renal structures you did in the Right Kidney.

Hydronephrosis.

Despite the limitation in direct stone visualization, the presence and grade of hydronephrosis can help to inform the management of patients presenting with renal colic. Patients with no hydronephrosis are at low risk for hospitalization or urologic intervention [8]. Moderate to severe hydronephrosis has poor sensitivity but 94% specificity for the presence of a stone. Patients with renal colic and moderate or severe hydronephrosis on POCUS are more likely to require a urologic intervention [9].

MILD

“Mild” Hydronephrosis occurs when there is dilatation of the renal pelvis without dilatation of the calyces. The renal cortex (parenchyma) is preserved and does not show any atrophy.

MODERATE

“Moderate” Hydronephrosis occurs when you have dilatation of the renal pelvis and of the calcyces, specifically the MAJOR and MINOR calyces. Mild cortical thinning may be seen. Thanks to The Pocus Atlas for these images.

SEVERE

“Severe” hydronephrosis occurs when there is significant/gross dilatation of the renal pelvis and calcyces resulting in renal cortical thinning. There will also be renal atrophy and loss of the borders between the renal pelvis and calyces.

Renal Abscess.

The main utility for POCUS in the evaluation of patients with pyelonephritis is the timely identification of underlying obstructive uropathy and complications such as pyonephrosis, abscess, or emphysematous pyelonephritis, which can expedite appropriate treatment. Chen et al. found retrospectively that POCUS detected significant abnormalities such as stones, hydronephrosis, or abscesses in 39.6% of patients presenting with acute pyelonephritis. [10]

Evidence of emphysematous pyelonephritis typically appears as a high amplitude/echogenic focus associated with distal “dirty shadowing” or low-level echoes and everberations caused by the near total sound reflection at the tissue-air interface, distinct from the echo-free shadow formed by calculi. [11]

The ultrasonographic appearance of renal abscesses can range from hyper- to hypoechoic focal masses or cystic structures, potentially with posterior acoustic enhancement [12]. If air is present within the fluid collection, a ring-down artifact may be present [13].

Mimics and Variants.

Renal cysts are common and can be found in 24 - 47% of the general population, with a higher prevalence in the aging population [14]. Cysts appear as circular or ovoid shaped, typically anechoic structures that demonstrate posterior acoustic enhancement [15]. Although commonly located in the periphery of the kidney, cyst can be found in the sinus where they can be mistaken for hydronephrosis. Because ultrasound can accurately detect cysts larger than 0.5 cm, POCUS practitioners will encounter cysts and must be able to characterise and distinguish them from similar lesions, such as hydronephrosis, solid masses, and abscesses [16]. While hydronephrosis progresses from the renal pelvis to the major and minor calyces and then to the cortex, cysts are cortical or parapelvic and do not follow this anatomic pattern [17, 18].

Solid renal masses may have cystic components but are mostly echogenic. The most common tumor is renal cell carcinoma, which is typically found in the periphery and may be somewhat difficult to identify since they are usually isoechoic and are poorly differentiated from the surrounding parenchyma. [19]

Author: Cristina Sorlini | Published: 21 October 2022

Reference.

Taus PJ, et al. Bedside Assessment of the Kidneys and Bladder Using Point of Care Ultrasound. POCUS J. (2022); 7: 94-104

Sibley S, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for the detection of hydronephrosis in emergency department patients with suspected renal colic. The Ultrasound Journal. (2020); 12(31): 2-9

Nepal S, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound rapidly and reliably diagnoses renal tract obstruction in patients admitted with acute kidney injury. Clinical Medicine (2020); 20(6): 541–4

Daniels B, et al., STONE PLUS: evaluation of emergency department patients with suspected renal colic, using a clinical prediction tool combined with point-of-care limited ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. (2016); 67:439–448

Fields JM, et al. The ability of renal ultrasound and ureteral jet evaluation to predict 30-day outcomes in patients with suspected nephrolithiasis. Am J Emerg Med. (2015). 33: 1402–1406

Wong C, et al. The accuracy and prognostic value of point-of-care ultrasound for nephrolithiasis in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med (2008); 25(6): 684–698

https://www.pocus101.com/renal-ultrasound-made-easy-step-by-step-guide/

Yan, J.W., et al., Normal renal sonogram identifies renal colic patients at low risk for urologic intervention: a prospective cohort study. Cjem, 2015. 17(1): 38-45.

Wong, C., et al., The Accuracy and Prognostic Value of Point-of- care Ultrasound for Nephrolithiasis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. (2018); 25(6): 684-698.

Chen, K.C., et al., The role of emergency ultrasound for evaluating acute pyelonephritis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. (2011); 29 (7): p. 721-4.

Allen 3rd, H.A., et al., Sonography of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. (1984); 3(12): p. 533- 537

Demertzis, J. and C.O. Menias, State of the art: imaging of renal infections. Am Soc Emergency Radiol. (2007); 14: 13-22.

Brown, N., et al., Emphysematous Pyelonephritis Presenting as Pneumaturia and the Use of Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Emergency Department. Case Rep Emerg Med. (2019);

Laucks, S.P et al., Aging and simple cysts of the kidney. Br J Radiol (1981); 54 (637): 12-4.

Baston, C.M., et al., Renal and Bladder Ultrasound, in Pocket Guide to POCUS: Point-of-Care Tips for Point-of-Care Ultrasound. (2018); McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY.

Reed, B., et al., Renal ultrasonographic evaluation in children at risk of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. (2010); 56(1): 50-6.

Cox, C., et al., My patient has abdominal and flank pain: Identifying renal causes. Ultrasound, (2015); 23(4): 242-50.

Lee, J. and M. Darcy, Renal cysts and urinomas. Semin Intervent Radiol. (2011); 28(4): 380-91.

Hansen, K.L., M.B. Nielsen, and C. Ewertsen, Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics (Basel). (2015); 6(1).

The Pocus Atlas. https://www.thepocusatlas.com/hydro-and-obstruction