Heart: Basics

Rationale.

WHY USE ULTRASOUND?

Focused echocardiography is a rapid and systematic assessment tool in the acute care setting and leaves aside the complex measurements of formal echocardiography.

The aim of focused echo is to provide a qualitative assessment of the overall cardiac function by answering specific simple questions (1).

LIMITATIONS: FOCUSED VERSUS COMPREHENSIVE

Formal echocardiography is a comprehensive assessment that involves almost every morphologic and functional aspect of the heart. This skill can only be acquired with extensive formal training under expert supervision, which is outside the practical achievement of most emergency practitioners. When a thorough echocardiogram is required, a formal study should be arranged (2).

The focused approach is simpler and comprises two-dimensional (2D) images without most of the more complex quantitative measurements; hence, it is also easier to master (3). It has been shown that a rapid goal-directed, focused study can be carried out with a limited amount of training (4). Focused echo has the added advantage that the clinician carrying out the exam is also treating the patient and, thus, is best placed to relate the echo findings to the clinical situation (5).

Anatomy.

Before attempting to acquire cardiac images, it may be necessary to stop and think about some anatomic features.

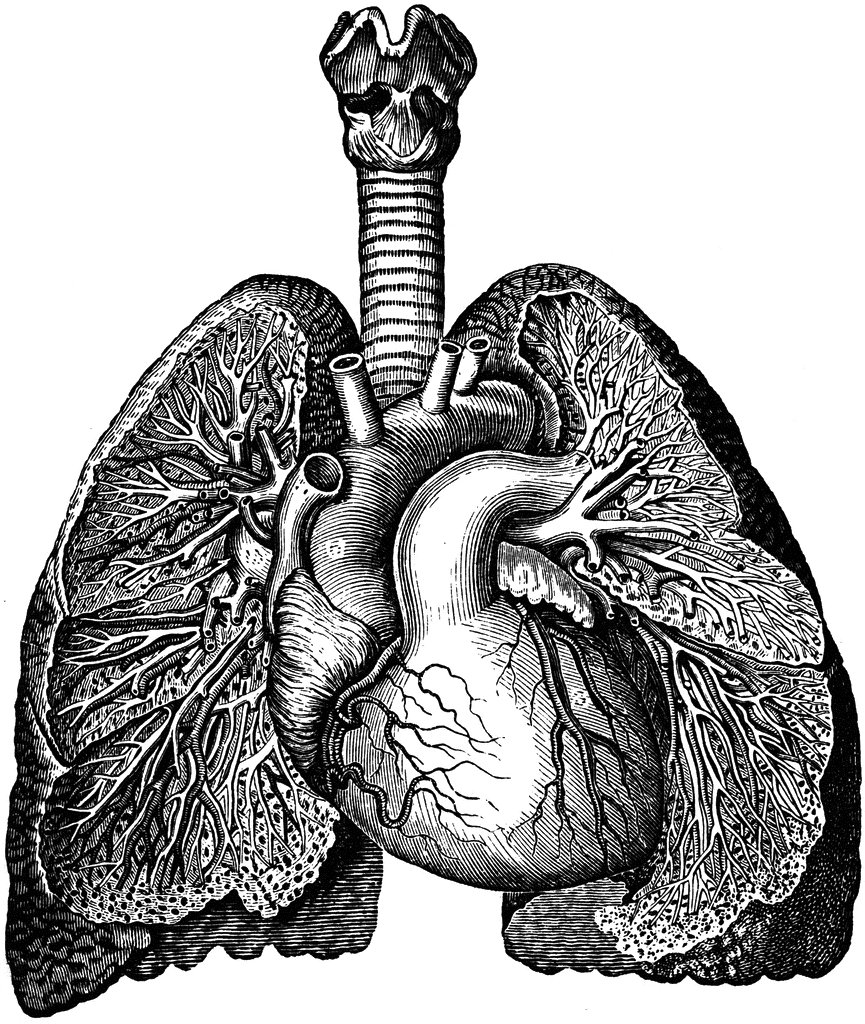

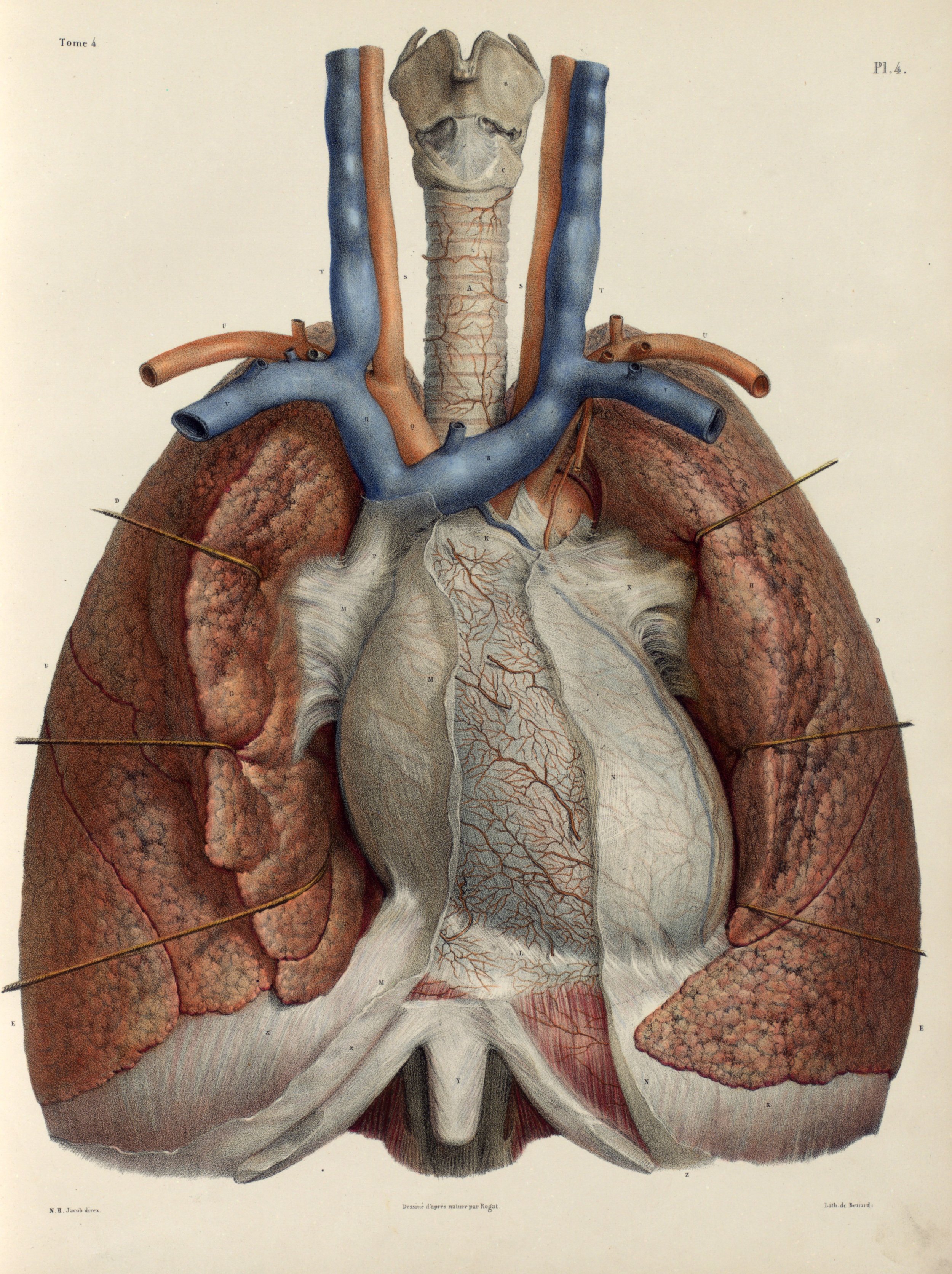

The heart lies in the mediastinum immediately under the sternum and chest wall. It extends from the second to the fifth intercostal space, oblique to the left, following a long axis that points from the base to the apex. The right atrium and ventricle are anterior in relation to the left chambers.

The main vascular structures, namely the vena cava, ascending aorta, pulmonary artery, and pulmonary veins, can be found at the base of the heart, where they enter or exit the different chambers. The pericardial sac surrounds the heart and can contain a physiologic amount of free fluid.

Settings.

PATIENT’S POSITION

The ideal patient position is left lateral, bringing the heart left to the sternum and closer to the probe; so that there is less shadowing to overcome. In the emergency department, however, the position is dictated by the clinical picture, and a supine or sitting approach may be more practical or even compulsory in some patients.

PROBE

Owing to the small window provided by the intercostal spaces to examine the chest, a small footprint phased array probe is ideal. If a cardiac probe was unavailable, a standard low-frequency curved probe could be an option, especially subcostal. The images will be suboptimal and difficult to obtain, yet may suffice to elucidate the presence of cardiac standstill and pericardial tamponade. More complex questions, however, will hardly be addressed by a curved abdominal probe, as this requires a combination of views and the capacity to assess, for instance, LV motion and contractility.

SETTINGS

Parasternal Long Axis View: The right ventricle is anterior and appears on the screen closest to the probe. The left ventricle is seen deeper to the right ventricle. Marking dot on the right. The apex of the heart points to the left of the screen.

Visualising cardiac fast-motion requires a ‘cardiac preset’ with a higher frame rate, which results in a less ‘jerky’ image. Such preset will also need a decreased dynamic range for the structures to appear more contrasted (black&white), which aids when performing chamber measurements.

This cardiac preset differs from the abdominal preset in the display orientation: the image is reversed, and the marker dot is now at the right of the screen, posing a challenge to the novice sonographer. For example, on the parasternal long view, the apex of the heart points to the left of the screen, not the right.

The Views.

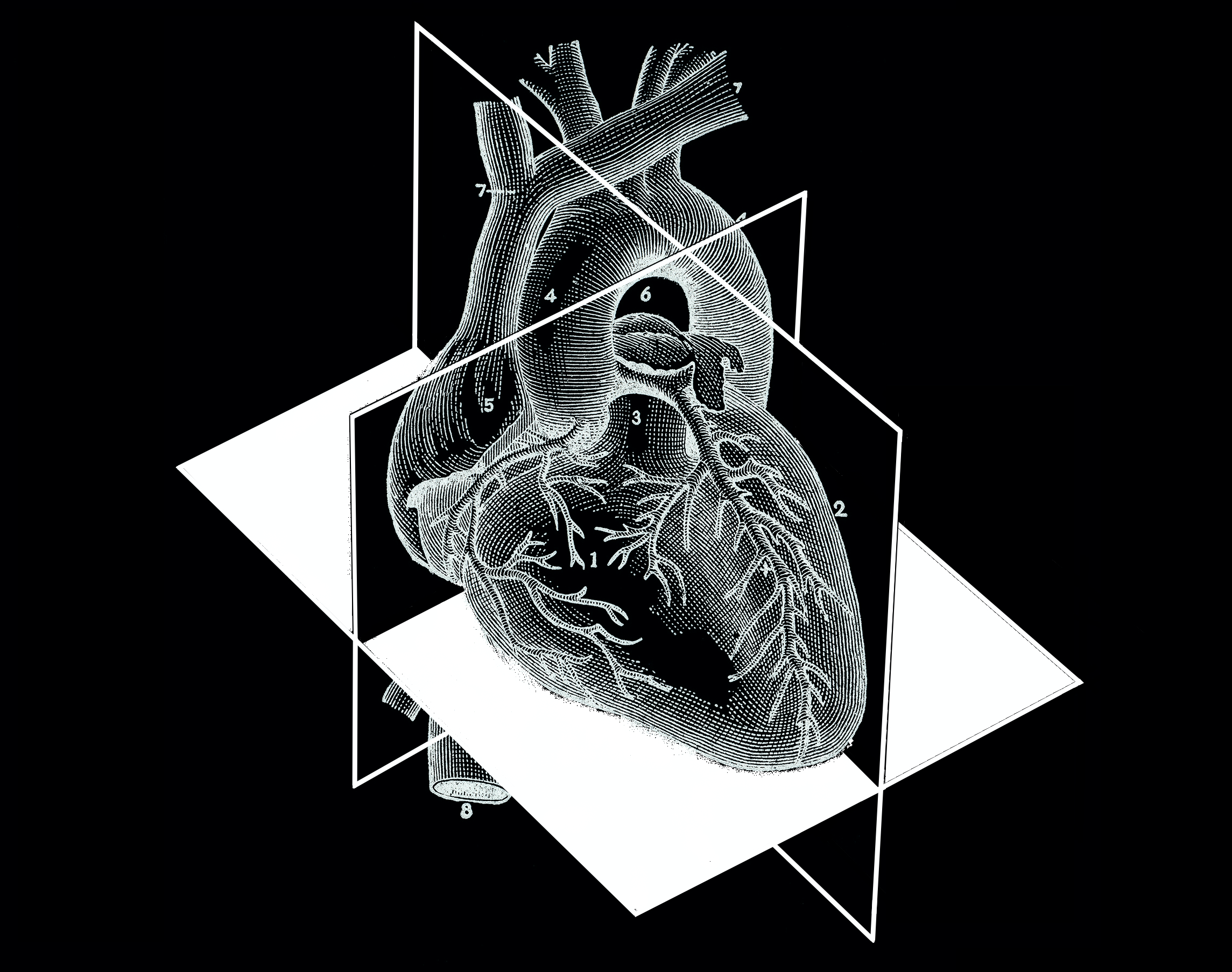

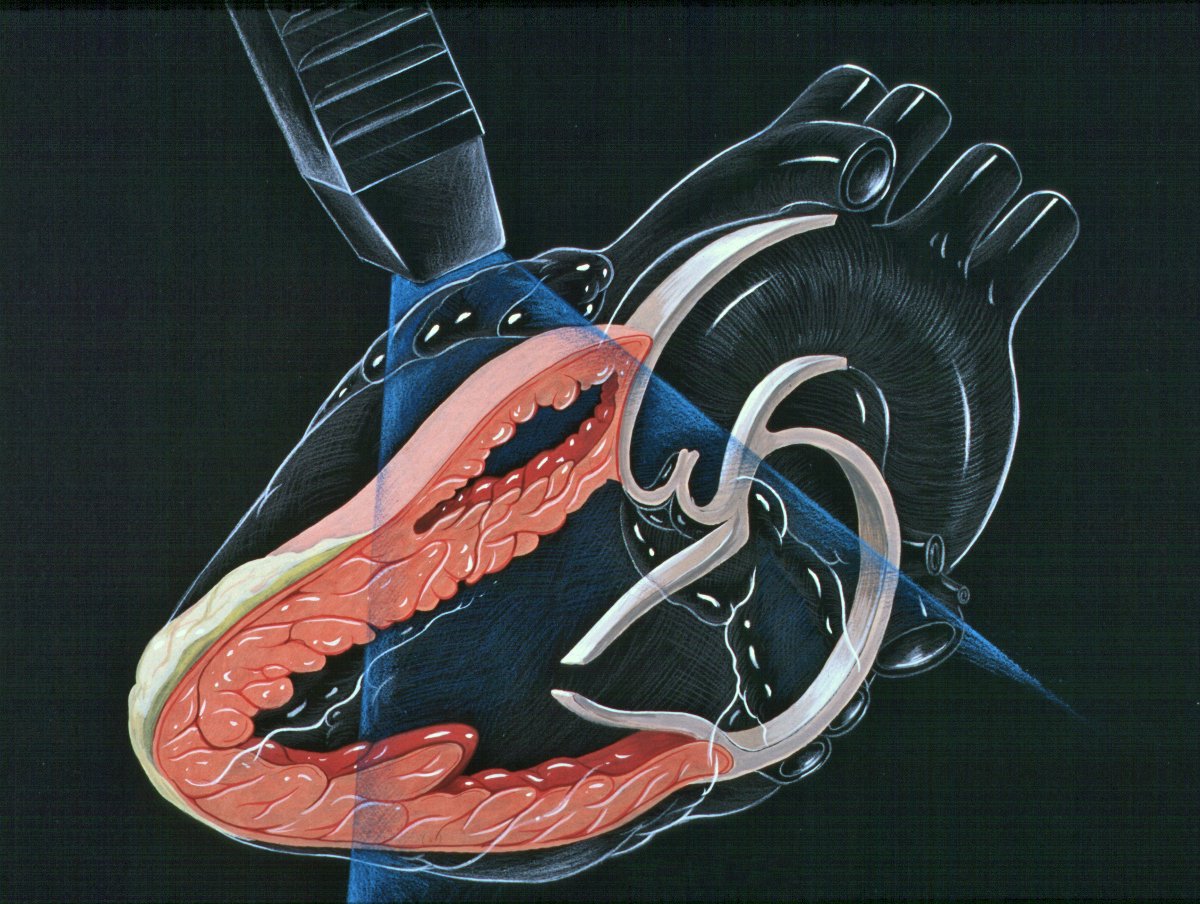

The heart is best described in axis and planes. Accordingly, there is a long axis going longitudinal from the base to the apex, and a short axis that is transverse to the former. The horizontal plane reveals the classic four-chamber image. It is important to note that as the heart itself has an oblique angle within the chest, these planes do not relate to the patient's body, yet are longitudinal or transverse concerning the direction of the heart.

In echocardiography, the heart is viewed in its long and short axis (parasternal views), as much as in a coronal plane going horizontally (white colour) in the long axis (apical and subcostal views).

Although there are more, this module will describe four views: two parasternal windows following either the long or short axis, and two 4-chamber views that see the heart in the horizontal plane (apical and subxiphoid). Given its clinical relevance and the intimate relation of the heart with the major vessels, this section will also describe the technique to assess the inferior vena cava.

PLAX

PARASTERNAL LONG-AXIS VIEW

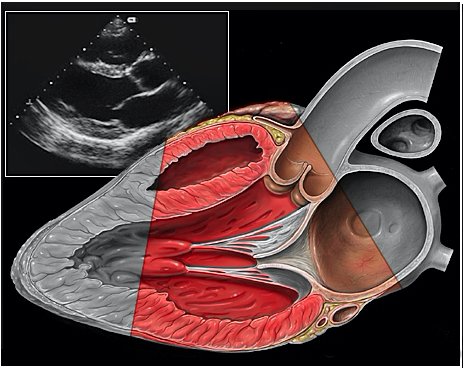

This is a versatile view and provides a considerable amount of information from different structures. It is useful to assess the left ventricle contractility, estimate the ejection fraction, and measure the aortic root size. It also gives insight into the chamber relationship (RV:AoRt:LA = 1:1:1) and differentiates pleural from pericardial effusion.

ORIENTATION & TECHNIQUE

The initial obstacle in obtaining a PLAX view is due to screen orientation in the cardiac preset. If the marking on the screen is on the right side, the marking on the probe should point to the right shoulder. If for any reason, the marking on the screen is on the left side, then the marking on the probe should point to the left hip. Either way, the probe will always follow the long axis and have the proper orientation.

Place the transducer at the level of the second to fourth left intercostal space. Scoping around this area will eventually reveal a pulsatile motion. After finding the heart, adjust the depth to include the descending aorta. Slightly rotate and fan the probe until it aligns with the heart’s long axis. Importantly, such alignment will provide an accurate sagittal view, avoiding oblique views that could overestimate or underestimate the size of the chambers.

LANDMARKS

A correct PLAX view will align with the heart’s long axis, producing a sagittal cut. On the screen, from the top, we see the right ventricle, the interventricular septum, the left ventricle with its outflow tract, the aortic valve and aortic root, and the left atrium. It is essential to look for the descending aorta, which appears in a transversal cut deeper to the LV.

PSAX

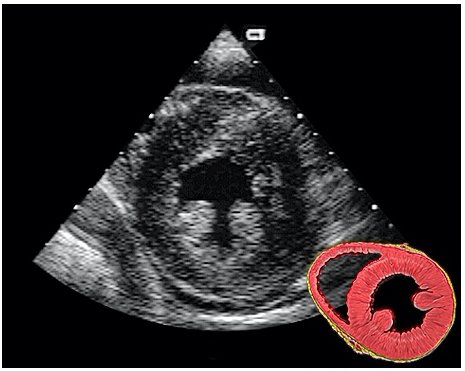

PARASTERNAL SHORT-AXIS VIEW

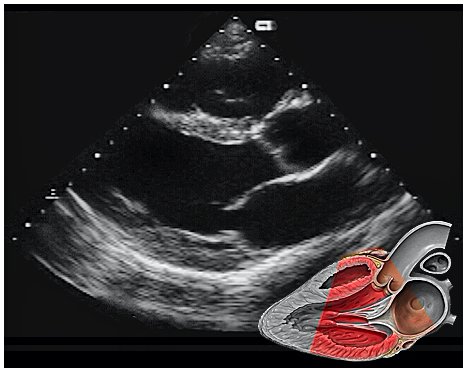

As the transverse (short-axis) images show the relative wall thickness and contractility, this view is the best for assessing regional wall motion. Also, the inferior portion of the view (papillary muscles) is ideal for comparing the relative size of both ventricles. In expert hands, the superior portion of the view allows evaluation of the aortic valve and RV overload.

ORIENTATION & TECHNIQUE

A good PSAX starts from a proper parasternal long-axis. Without sliding or displacing the probe, rotate it 90º clockwise so the marking points to the left shoulder. The resulting image is a transverse cut to the heart’s long axis, hence, a short-axis view.

While maintaining the short axis, sweep or gently fan the probe along the long axis to obtain a series of ‘sectional’ views of the LV and RV.

PITFALLS

Common mistakes when acquiring a PSAX view are starting from an oblique, poorly achieved PLAX (not parallel to the long axis), leading to a 'false' short axis, and tilting the probe instead of sweeping it along the long axis, which ends up distorting the image.

A4C

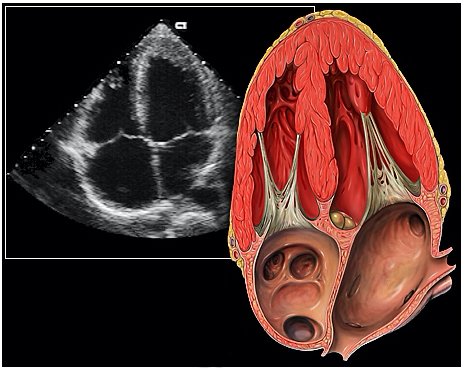

APICAL FOUR-CHAMBER VIEW

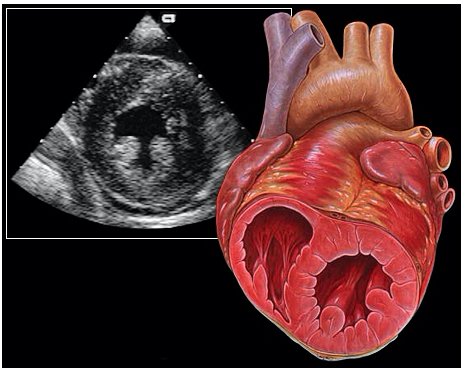

This view looks at the heart from the apex. When done properly, it achieves a horizontal cut of the heart that demonstrate all four chambers simultaneously. Consequently, its main utility is to assess the relationship between LV and RV. Beware, differentiating the chambers by ventricle size or thickness is not recommended, and it could lead to confusion in case of RV enlargement.

ORIENTATION & TECHNIQUE

Place the transducer at the apex beat and angle it towards the right scapula. The correct image results from sliding the probe until the interventricular septum is in the middle of the screen, vertically dividing both sides of the heart. If using a cardiac preset, the probe’s marker points towards the patient’s left arm. Simpler, in this view, the probe notch should meet the marking on the screen, which is fundamental to avoid confusion.

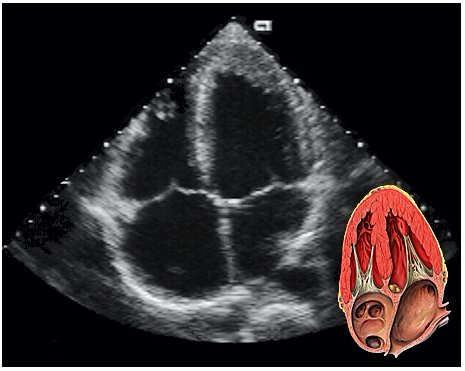

SX

SUBXIPHOID VIEW

This is the standard window taught in FAST and might be the only one available during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). This view uses the liver as an acoustic window. To obtain good visualization is essential to handle the probe almost parallel to the anterior abdominal wall, trying to place it under the xiphoid process, pointing to the left shoulder. A deep inspiration or half inspiration can be useful to bring the heart closer to the probe and improve visualisation.

Remember that in the cardiac preset, the screen marking is on the right side. As a result, and unlike the FAST exam, the probe marking points towards the patient’s left. This view is used mainly to look for pericardial fluid, but it also provides information about ventricle size, chamber relationship and valvular abnormalities.

IVC

INFERIOR VENA CAVA VIEW

Coming from the subxiphoid view, scan longitudinally and slightly to the right of the body’s midline, with the orientation marker towards the head. Identify the landmarks and differentiate between the aorta and IVC by dragging the probe to the sides. Then slide the probe upwards, following the IVC as it traverses the diaphragm to enter the RA. Measure the IVC about 2 cm caudal to the RA entrance or 1 cm caudal to the hepatic vein inlet, but not at the level of the diaphragm. Measure the maximum IVC diameter, which will be in expiration, in two planes. Then measure the minimum IVC diameter using the sniff test: ask the patient to sniff quickly, causing the intrathoracic pressure to fall rapidly and a normal IVC to collapse. M-mode has been proposed to capture maximum and minimum diameters on a single image; however, this is not recommended, considering the IVC is displaced upwards with the respiratory movements (2).

Author: Felipe Urriola | Review: Tim Harris | Published: January 2023

Reference.

FUSIC Heart Training Pathway. Intensive Care Society. https://ics.ac.uk/product/heart.html

Bowra, Justin; McLaughlin, Russell; Atkinson, Paul; Henry, Jaimie. Emergency Ultrasound Made Easy, Third Edition. 2022. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. (1993). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

Randazzo MR, Snoey ER, Levitt MA, Binder K. Accuracy of emergency physician assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and central venous pressure using echocardiography. Acad Emerg Med. 2003 Sep;10(9):973-7. PMID: 12957982

Basaure, Carlos; Clausdorff, Hans; Riquelme; Felipe. Ultrasonido Clínico, First edition. 2018. Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Universidad Católica de Chile.